I have been working for On the Road Experiences since 2013. I started as a host…

What does a “host” do? As a journey host I oversee the whole journey from greeting guests on the first day until we all say goodbye on the last. I am responsible the service we provide and for the experiences guests enjoy; our aim is to make each journey enjoyable for all parties involved.

My role has grown over the years, and now I enjoy researching new itineraries, enhancing our existing journeys, and meeting guests before they join a trip and developing the German market. Peter gives my colleagues and I the chance to grow – sometimes it seems that every day I find myself with a new project, which makes me busy and happy!

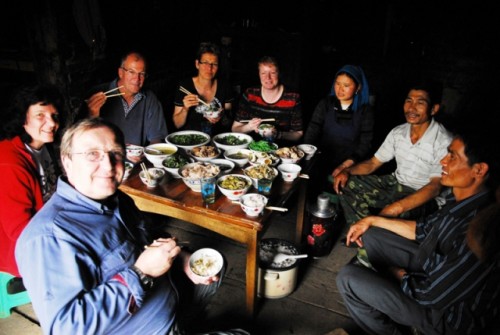

Looking back at all the journeys I have hosted, I remember a lot of laughter and happiness, and my hard-drive is full of pictures of sunsets, beautiful landscapes and people. Two things that I can’t capture on film, though, are the hard work and long days that go into making each journey a success.

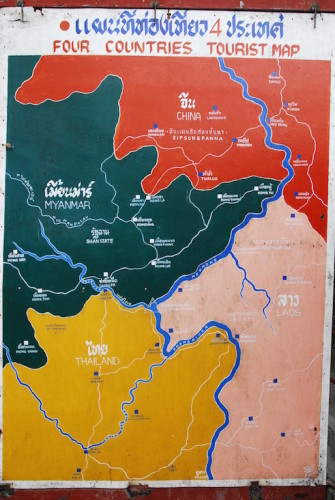

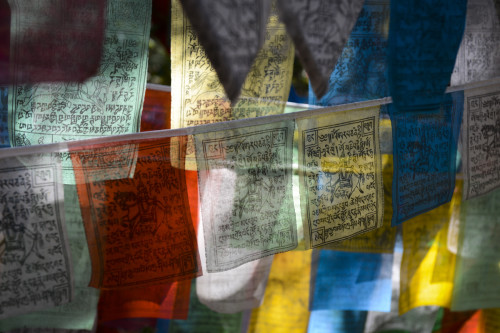

Explaining my job to friends isn’t easy, because it is not at all like being on holiday, and neither is it “just” being a tour guide. We have to work with the fact that on each journey there will be many unforeseen events along the way – hopefully these will be fun things, such as yaks on the road or coming across a colorful local festival, but they might include road closures or even landslides.

In March, for example, we got held up by market day in a small village on the way to Puzhehei, where all the roads were gridlocked with trucks both big and small.

Nobody could move until the stallholders began to clear up two to three hours later. Thinking of it now, the pictures it brings to my mind are of our guests sitting on the side of the road, relaxing – one smoking a cigar, and chatting with the market-goers.

Our drivers got stuck in, handling and coordinating the traffic while the policemen lolled about drunk on the pavement! I love that our guests and my colleagues managed to make the most out the afternoon and still find something good in a situation that wasn’t so good. It was very hot that day. As I tried to get cold drinks to keep us all refreshed, I ended up going from shop to shop as I discovered that none of the fridges were working! Finally, in a tiny shop I found cold beverages and local snacks, which I took back for us all to share.

This kind of experience is a good reminder for everyday life – of course I had all sorts of worries going through my mind: “What if we’re stuck here forever? “How long will this traffic jam last?” “What are our customers thinking?” “Will it get dark before we arrive?” “Are there any short cuts we could use?”, and so on and on… And I wished that we might have had a smoother journey on that day, but the reality is that life doesn’t always go to plan, and sometimes you just have to make the best most out of whatever happens!

Curiously, almost without fail, it is the unforeseen events, well handled, that our guests remember the most after we return home. Sometimes it’s the bends in the road that are the most memorable and meaningful!