Tag Archives: China

Posted on 2 Dec, 2015

Everyone has heard of Shangri-La. Even for those who have not read James Hilton’s classic Lost Horizon, the name evokes visions of an earthly paradise tucked away amongst soaring mountain ranges, where humans live long and peaceful lives amidst pristine, otherworldly surroundings.

In northwest Yunnan there is a Tibetan town, historically known as Zhongdian. Perched at the south-eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau and astride the main route to Tibet proper, the small town has long been a trading post and meeting point between Yunnan’s lowlands and highlands. Zhongdian’s compact old town was once filled with thick-walled Tibetan houses, yaks grazed in verdant fields around the town and stupas decorated the surrounding hillsides – undeniably picturesque, but still a far cry from Hilton’s fictional paradise.

Just over ten years ago Zhongdian’s enterprising mayor decided that since no one knew where Shangri-La was, it might as well be in Zhongdian. A pretext was fabricated (certain geographical features outside the town are said to resemble those mentioned in the novel) and Zhongdian was duly renamed Shangri-La, or Xianggelila in Chinese.

The new name and a new airport spurred a building boom that has seen old Zhongdian transformed into a somewhat ugly, modern town. Then, in early 2014 a devastating fire burnt much of the old town to the ground. Whatever faint resemblance the place may once have had to the Shangri-La of fiction, it has now gone for good.

So did the idea of Shangri-La go up in flames along with Zhongdian’s timber-framed old town?

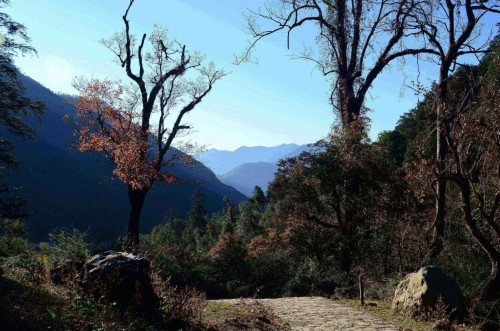

The north-westernmost region of Yunnan is formally called the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Shaped like a triangle balancing on one point, the region is composed of three counties; Shangri-La (with Zhongdian/Shangri-La at its centre) in the east, Weixi in the west and Deqin at the uppermost tip of the triangle. If you are looking for Shangri-La, stop briefly in Zhongdian/Shangri-La, if you must, but make sure you leave time to explore Diqing’s beautiful hinterland. While it might not exactly match Hilton’s description, the region is so lovely and holds such natural bounty and variety that any such qualms will quickly be forgotten.

Diqing is home to at least ten ethnic minorities. The largest of these is Tibetan, but there are also the Lisu, Naxi, Bai, Yi, Hui, Pumi, Miao, Nu and Drung, among others. Each speaks its own language, practices its own and religion, and wears – for the everyday, not for tourists’ benefit – its own traditional clothing. People are friendly and welcoming, especially in the remoter parts of Diqing where tourists are still rare.

Diqing straddles one of the world’s most bio-diverse regions, the so-called Three Parallel Rivers, named for a short-range geographical accident that sees three of Asia’s great rivers – the Yangtze, the Mekong, and the Salween – churn through lush, parallel valleys for several hundred kilometres. The Three Parallel Rivers region is home to many exotic and endemic species of flora and fauna. One of the most endearing is the Yunnanese snub-nosed monkey, one of the rarest primates on earth. Incredibly, it is easy to spot (and photograph) in a sanctuary of old-growth forest that lies in the mountains between the Yangtze and Mekong valleys.

The region’s human heritage and geography is no less rich and varied with a long list of little-visited, yet spectacular attractions. Each Sunday in the tiny village of Cizhong, a Tibetan priest holds mass in a nineteenth-century church built by French missionaries. Further north, there is the massive Meili Snow Mountain range. The highest peaks rise to over 6,000 metres, making for impressive prominence over the river valleys to the east and west. The highest peak is sacred 6,740-metre-tall Kawagebo, which – in deference to local religious beliefs – has never been summited.

While the mountaintops are left to local gods, it’s still possible to feel the magic of travelling through the mountains and climbing towards distant peaks on the ascent from lowland Yunnan to Diqing. Some may opt to fly straight into Zhongdian/Shangri-La, at the risk of both altitude sickness and a dislocating sense of culture shock. However, far better to travel overland, slowly acclimatising to the thinner air and absorbing the gradual change in your surroundings as the familiar trappings of modern life give way to something gentler and altogether rarer. By the end of your journey, you might just feel that you have, indeed, glimpsed Shangri-La after all.

If you would like to go in search of Shangri-La for yourself, you may want to take a look at this travel idea here.

Posted on 23 Nov, 2015

I want to write about Tibet, but I’m struggling with where to start. Should I begin by describing the raw beauty of the Himalayas? Maybe with the profound way that Buddhism permeates the Tibetans’ daily lives? Or perhaps I should start with the rigours that are inevitably involved in a journey on the Tibetan Plateau?

This forbidding region draws me to it in many ways, but it boils down to the following; the pursuit of adventure, a love of mountains, the challenge of overcoming adversity, and witnessing the Tibetan people’s devotion.

Above all, to me Tibet stands for adventure. In exchange for moving myself out of my comfort zone, I know that I will come home with unforgettable memories.

The photo shown here is from one of many such adventures, and taken on my 21,000km journey through China in a Caterham Super 7.

It was July 2007 and early rains had swollen a nameless river in eastern Tibet, sending it gushing across the road. Attracted by the odd sight of a yellow sportscar on this remote stretch of road, three passersby rolled up their sleeves and volunteered to help Miss Daisy (the Caterham) and I through the water. When you scream ‘push’ and three kind volunteers heave you through an icy cold river, you won’t forget it!

Beyond the thrill of adventure, there is the magnetic pull of the mountains. I grew up in the Austrian Alps and thought them magnificent – until I went to Tibet, that is. In Austria you reach sky at 2,000 metres above sea level. In Tibet there are cities with airports and golf courses at that altitude. The Tibetan highlands start where the Alps end, more or less. The plateau is, almost literally, quite out of this world.

But while Tibet’s mountains – from Mount Everest on down – lend the landscape an unparalleled drama and beauty, the region’s high altitudes also make plateau life and travel uniquely challenging. Lhasa’s iconic Potala Palace may seem an appealing place to visit on your first day in the Tibetan capital, but climbing the staircases to the entrance is best left until the end of your trip when you are properly acclimated.

Perhaps the Tibetans’ profound Buddhist faith is related to the challenges of living at such altitudes. Almost every time I find myself in the Tibetan world, sooner or later I encounter people making the arduous pilgrimage to Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple. Each pilgrim will prostrate themselves, get up, walk three steps, and prostrate again (in Chinese this is called 磕长头). This slow progress continues, not for a hundred meters, not for one kilometer, but for hundreds – if not thousands – of kilometers.

Weatherbeaten, dirty, exhausted, and yet with their broad smiles hinting at inner bliss, the pilgrims have retained a depth of faith that many of us have long since lost. I’m not a religious man, but I never fail to be moved by others’ devotion. Add to this the outer trappings of Tibetan Buddhist ritual – monks chanting by flickering lamplight, prayer flags snapping from mountain passes and timeless festivals – and this is clearly one of Tibet’s many attrations for me and many others.

Some places offer one of these drawcards, perhaps one destination offers mountain adventure, while another posseses a unique culture, say, but few offer such a beguiling combination as the Tibetan Plateau. It is small wonder that this special place has attracted generations of adventurers and romantics…

What is it that draws you to Tibet?

* * *

If you agree with me about Tibet’s many and varied attractions, you might like to read more about our upcoming Tibetan journeys.

Mountain-lovers will be interested in Roads on the Roof of the World, a fantastic 8-day itinerary that runs from the Tibetan heartland to Mount Everest Base Camp. The 11-day Tibetan Highlands is an epic journey from Kunming to Lhasa overland across the beautiful and rugged eastern foothills of the Himalayas. Both will have departures in spring 2016.

Posted on 22 Nov, 2015

The first trip I led with Ron Yue, our team’s professional photographer, covered familiar ground. I had completed the itinerary through southern Yunnan several times before, both for research and with groups of guests, so I knew what to expect. Except that I didn’t.

Over the course of our week-long trip I discovered that travelling with a photographer is quite different to travelling without one. The pace is a lot more leisurely, for one thing, with plenty more photo stops, both scheduled and impromptu. The conversation over dinner tends towards discussion of f-stops and exposure compensation, and you return home with distinctly better quality holiday snaps. But the most significant – and unexpected – difference was that I discovered a fresh new beauty in those familiar places, thanks to Ron and to my camera.

Following Ron’s example and with his coaching, our group of photographers became more and more observant of our surroundings as we travelled. I found myself stopping more, enjoying scenes and noticing details that would have passed me by before. An everyday market was suddenly filled with unexpected moments of loveliness – a child playing amongst piles of chilli peppers lying around her mother’s stall, or an elderly lady deftly binding piles of damp, field-fresh herbs into bundles ready for sale.

If photography can help us to appreciate somewhere as down-to-earth as a local market, the impact of a truly splendid sight is magnified many times for the photographer. On that first trip, we visited one of Yunnan’s many photogenic landscapes, the Yuanyang rice terraces. Patterns emerged where before there were none, light danced over the landscape in a newly entrancing way and fleeting moments captured on film (or in pixels) still give me pleasure now, five years later.

By opening our eyes to the beauty that surrounds us, and by providing a keepsake to remind us of treasured moments, photography is a wonderful complement to travel, whether we’re documenting a family holiday or a once-in-a-lifetime expedition, whether we’re in the wilds of Yunnan or in the middle of a city. But maybe we can also bring that awareness back home, to help us reconnect with the beauty of the everyday, from the reflection of a vivid sunset on an office building to the warm smile of a loved one.

While our original photography itinerary (The Exotic South) took in just one of Yunnan’s iconic landscapes, the province has many more in store – as Ron says “there is an incredible diversity of colours and landscapes in Yunnan – plenty to keep a photographer busy!” Now, we have introduced a new photography journey that features three of the most beautiful landscapes on a single itinerary, Red Earth and Fields of Gold.

From the vivid red earth of Dongchuan to the limestone karsts and blazing yellow rapeseed fields around Luoping (and one of our favourites, the Yuanyang rice fields) generations of local people have dramatically added their own imprint to landscapes across eastern Yunnan, creating patterns that fuse the manmade with nature and creating scenes found nowhere else.

Posted on 16 Nov, 2015

When we leave the highway behind and opt to discover the world from its back roads, curious things can happen. More often than not, those things can give us a glimpse of what makes local people tick.

A recent research trip of ours ended in Shangri-La, the main settlement in Yunnan’s ethnically Tibetan northwest. On the day of our team’s departure, we caught a taxi to the airport. Our driver was a burly Tibetan gentleman with an infectious laugh, who had somehow managed to squeeze himself into the cab’s cramped driver’s seat.

On the outskirts of Shangri-La a large white stupa stands at the centre of a roundabout – seemingly a typical piece of Chinese municipal architecture. As we joined the roundabout, the driver turned left instead of right and calmly circled the roundabout clockwise, against the usual flow of traffic.

Mercifully, nothing seemed to be about to crash into us. Still, we asked with some alarm, “What are you doing?! Aren’t you supposed to go the other way around?!”

“No, in the mornings we can go around it this way,” he assured us, smiling, “because the stupa is holy, isn’t it?” For Tibetans circle all holy things – roundabout stupas included – clockwise, in a show of respect.

“And what if a non-believer should come the normal way around?” Peter pursued the argument to its inevitable conclusion.

“Well, there might be a crash,” he said, his expression deadpan.

My mind wanders terribly. While I might look as though I’m sitting at my desk or riding the subway, in my head I’m watching crowds celebrate Saga Dawa in Gyantse or cycling across New Zealand’s Southern Alps – remembering long-ago trips and planning future travels.

While I’ve always thought of these daydreams as being one small step away from procrastination, recent psychological research shows that by reliving fond memories and anticipating future experiences I’ve actually been enjoying one of the few ways in which money can buy happiness.

The relationship between money and happiness has long been a source of debate. Reams of psychological studies have been produced on the topic since the 1970s, when a group of Californian academics discovered the Easterlin paradox – that money does make people happier, but only up to a point. Once our basic needs have been taken care of, it seems that it’s up to how we spend any surplus that makes the biggest difference to our happiness.

Research has found that the best way to do this is to invest your money in experiences – whether that means concert tickets or cooking classes, the holiday of a lifetime or a daytrip – rather than material possessions.

Logically, buying something would seem to make more sense – a hi-tech watch or a beautiful book will be around long after an experience has ended, after all. However, this logic glosses over several facets of human nature, which combine to turn that thinking on its head.

For one thing, we easily take things for granted. It’s not long before we get used to a shiny new toy and it becomes part of the background. Our levels of happiness soon return to where they were before, a process psychologists call hedonic adaptation.

While material goods deteriorate with time – getting scuffed and scratched – the memory of a pleasant experience improves with age. Even a bad experience can become a good story with enough retelling and time, and in this way fleeting experiences can become an ingrained part of our identity in a way that a possession rarely does.

Apparently even the way we anticipate experiences and purchases is different. Psychologists found more positive interactions amongst people queuing for concert tickets than among those queuing to buy smartphones, for example. Waiting to buy a new gadget tends to fill us with impatience, rather than anticipation, as I’m sure many of us have found!

Instead of giving in to the desire for impulse purchases and instant gratification, we can wring more enjoyment out of spending our hard-earned money by planning purchases far in advance. As the saying goes, “anticipation is the greater part of pleasure” – especially when it comes to experiences.

Shared experiences also bond us to others in a way that a mutual preference for a certain brand does not. While owning a 4K TV might give you something to talk about with another 4K TV-owner, it won’t make for an instant connection in the same way that, say, having climbed a mountain together would.

So, the lessons seem to be: buy experiences, not things; plan far in advance to maximise the pleasure of anticipation; enjoy recalling past pleasures – and keep daydreaming.

To read more about this topic, visit:

The Atlantic: By experiences, not things

Fastco: The Science of why you should spend your money on experiences not things