Hemmed in by culinary big-hitters, the cuisines of Cambodia, Burma and Laos are little known outside their homelands. This is undeserved, but it does mean that delicious surprises await adventurous diners in each of the three countries…

Tag Archives: Myanmar

Posted on 22 Jun, 2017

Thanks to long tradition and a shaky power supply, handmade industries thrive in Burma. We take a look at – appropriately enough – a handful…

Posted on 6 Jun, 2016

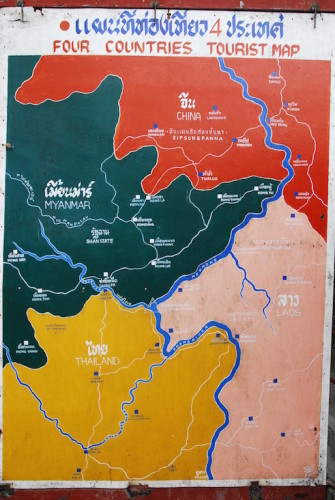

In October 2008, my wife Angie and I spent a few days in northern Thailand. While visiting this part of the Golden Triangle, we chanced upon a rusty map of the region. “Look,” I said to Angie, “two months ago I was here,” as I pointed to Xishuangbanna, the southernmost region of China’s Yunnan Province. (‘Xishuangbanna’, 西双版纳, is the sinicised version of the Thai word Sipsong Panna ( สิบสองปันนา) and means ‘twelve thousand rice fields’.)

“So close, eh?” Angie mused, “I wonder whether you could drive from there to here. Wouldn’t that be something?!”

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I replied, “There’s borders to cross and who knows if there’s even a road.” Having only just managed to organise our first driving journeys in China, the idea of crossing borders seemed, to me, unfathomable. In those days, whenever an idea came up, my brain was inevitably troubled by the question of how to make it happen, and from that often flowed a stream of reasons why it couldn’t be done. Angie, by contrast, is seldom bothered by such details.

Later that day I reluctantly pursued the idea with her. Wouldn’t it be something to drive from the foothills of the Tibetan Plateau in northern Yunnan down through Laos and the Golden Triangle to Chiang Mai, and to see China merge into South-East Asia, turn by winding turn? It was a powerful idea, but “how?”

***

I grew up in another Golden Triangle of sorts, in Bregenz, a small town by the eastern shore of Lake Constance where Germany, Austria, and Switzerland meet. No opium poppies there, I can assure you: the only sources of inspiration are reflections in crystal-clear lakes and the herb-scented mountain air.

Shopping in Switzerland? Lunch in Germany? Dinner in Austria? All in one day? Easy! As I child I regarded driving across borders as an everyday occurrence, but since moving to Asia I have gained a newfound appreciation for the romance – and administrative complexities – that such overland journeys can inspire.

***

Fast forward to April 2009. Angie and I have just landed in Shangri-La. The sky is overcast and snowfall has dusted the hilltops. While eating breakfast we meet the hotel manager and tell her about the journey we are about to make. Her eyes light up, “If you enjoy driving, then you must take the back road to Lijiang – let me show you…” I finish my toast in one bite and drain my coffee cup while Angie knocks back a motion sickness pill. And then we’re on our way.

The main road from Zhongdian to Lijiang is shown on my map as a thick red line. The road that we take is shown as a single pencil-thin line, snaking between the two towns. The hotel manager was right – the road is incredibly beautiful, winding over high passes before descending to the Yangtze at Tiger Leaping Gorge, where the river roars through a deep gorge beneath looming cliffs.

After arriving in Lijiang that evening, we wander the cobbled streets, bemused at the sheer number of people visiting this UNESCO World Heritage Site. From Lijiang we drive south along excellent highways to Dali, on the shore of Lake Erhai, and then to Kunming and south again to Jinghong, the largest town in Xishuangbanna.

By the time we arrive in sleepy Jinghong, with its palm tree-lined streets and Thai-style temples, it’s clear that we are on the edge of South-East Asia. The region’s main ethnic minority, the Dai, are closely related to the Thais and in the countryside we drive past groups of sarong-clad Dai women with flowers in their hair.

From Jinghong we continue our drive on another wonderful road to the China–Laos border at Mohan, where we make a bit of history: Angie and I are, according to everyone we ask, the first Westerners to drive a China-registered rental car across this border. What I had taken for granted back in the “Golden Triangle” of my youth does, indeed, mean making history here…

In Laos, Route 3 connects the China-Laos border with Huay Sai on Laos’ border with Thailand, cutting south-west diagonally across the country. At that time, Route 3 had been recently rebuilt, and the modern road contrasted starkly with the villages it runs through, where villagers’ lives seem untouched by the twenty-first century.

Later the same day we arrive at Huay Sai and take a rickety looking car ferry to Chiang Khong on the Thai side of the border. After a long day – driving in three countries and over 400 kilometres – Angie and I treat ourselves to a stay at the lovely Anantara Golden Triangle resort.

The next morning, wholly refreshed, we drive back up to the map of the Golden Triangle, where Angie had had her idea six months previously. We look at the battered map in its rusty frame before turning and gazing out towards Burma and Laos, shaking our heads and agreeing “Now, that really was something…”

Never, ever let questions of “How?” stand in way of pursuing your ideas!

Since that first trip, we now have multiple crossing-border itineraries in Asia allowing you to step into our footsteps:

- Yunnan via Laos to Thailand

- From Shangri-La to the Lanna Kingdom is exactly the itinerary that Angie and I explored in 2009.

- From Yunnan to the Lanna Kingdom starts “further down” in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, but includes the “Mirrors of God” Yuanyang rice terraces, a must-see once in your life.

- Yunnan via Laos to Vietnam – Our Summit to Sea itinerary takes you from one UNESCO World Heritage old town, Lijiang, in Yunnan to another, Hoi An, right by the South China Sea.

- Burma – Our From the Golden Triangle to the Bay of Bengal itinerary is a magical exploration of Burma, including out-of-the-way, hidden gems and well-known, must-see stops.

Posted on 22 Mar, 2016

Burma’s jungles hide fabulous reserves of precious stones. Mines around the town of Mogok in Mandalay Division produce much prized “pigeon’s blood” rubies and beautiful sapphires. In Kachin State, Hpakant’s vast open-pit mines – visible on Google Earth – produce the world’s finest jadeite. And yet, rather than “Land of Rubies” or “Land of Jade”, Burma is known as the “Land of Gold”.

One reason, at least, is obvious from a casual walk around any Burmese town or village. Keep your eyes open, and the chances are that within a couple of minutes you’ll either spot the burnished gold of a pagoda at street-level, or see one glinting from a nearby hilltop.

Burma’s paya – a word usually translated as “pagoda”, although the majority resembles stupas more than Chinese-style pagodas – are almost universally covered with gold leaf or gold paint. Coating and recoating religious buildings with gold is one of the best ways for the building’s sponsors to earn religious merit.

Elsewhere, the gold covering is more of a collective effort, with worshippers queuing to buy tiny squares of delicate gold leaf sandwiched between sheets of tissue. Mandalay’s Mahamuni Buddha is a good example; the lower part of this revered Buddha statue, believed to be one of a handful cast during Buddha’s lifetime, has slowly been obscured by layers of gold leaf applied by male devotees (women must watch the action on a television screen outside). The gold is now estimated to be between 20–30cm or almost 12 inches thick!

One of the most fascinating places I visited on my research trip to Burma was one of Mandalay’s gold leaf workshops. Considered a sacred craft, the leaves are handmade by a process that has changed little for centuries. First, an ounce of gold is placed in a bamboo paper wrapper and pounded with a heavy hammer for 30 minutes before being cut into six smaller pieces. These pieces are then stacked and the process is repeated again and again until the sheet reaches the requisite thinness, as you can see in the following video:

Crafting gold leaves is hard, but it pays well and, according to Buddhist tradition, buys good karma. Only men are allowed to do the hammering, taking up the job at the age of 16 and retiring in their mid-forties when their bodies can no longer endure the work. Women work at cutting the gold leaves, a less respected role than the men’s. Both men and women work in stuffy, wind- and draught-proof rooms to cut the feathery sheets of gold leaf into smaller pieces.

The second and less immediately obvious reason behind Burma’s golden nickname is that both the Burmese and the Mon believe that a region of Lower Burma was once the site of Suvarnabhumi, a “Golden Land” mentioned in early Buddhist texts.

The town of Thaton in Mon State is supposed to have sat at Suvarnabhumi’s heart. Once the capital of a wealthy Mon kingdom, today Thaton is a sleepy little market town, where the only signs of a “golden land” are the pagodas that glint from the ridge behind the town, and the large Shwe Saryan pagoda complex next to the bus station.

As you can see, both of the reasons why Burma is known as the “Land of Gold” are intimately connected to its people’s strong Buddhist faith. Another story I was told during my trip attests to this strong link: many Burmese families do not have savings accounts, not because they don’t have any money to save, but rather because any surplus each month is spent on gold leaf and stuck on temple statues – savings for the next life, rather than this one, as it were…

Please click this link to our “A Burmese Journey – From the Golden Triangle to the Bay of Bengal”, that features a visit to a gold leaf workshop in Mandalay.

Posted on 2 Mar, 2016

When I was working on The Rough Guide to Burma, I spent a week staying in a hotel in Hpa-An, Kayin State’s laidback capital, while I explored the surrounding region. One of my fellow guests was a slight, red-haired German man who wore wire-rimmed spectacles and a striped Kayin longyi, and spent afternoons drinking tea and reading on the hotel’s shady balcony. Intrigued as to why he didn’t seem to be going anywhere – other backpackers moved on after two or three nights – I eventually struck up conversation with him to find out why.

When I was working on The Rough Guide to Burma, I spent a week staying in a hotel in Hpa-An, Kayin State’s laidback capital, while I explored the surrounding region. One of my fellow guests was a slight, red-haired German man who wore wire-rimmed spectacles and a striped Kayin longyi, and spent afternoons drinking tea and reading on the hotel’s shady balcony. Intrigued as to why he didn’t seem to be going anywhere – other backpackers moved on after two or three nights – I eventually struck up conversation with him to find out why.

The man was actually on his third week in Hpa-An – this being the first major town he’d reached after crossing the border from Thailand. He’d arrived from with a two-week visa that he had used before returning to Bangkok for a second visa, which he was halfway through at the time of our conversation. “I just like to travel this way; I take a month off each year, and when I reach somewhere nice I’ll stop for a couple of weeks and spend my days exploring slowly and relaxing.”

Now, I write a blog that’s nominally about slow travel – a style of travel that I find very appealing and very unachievable, as I always end up in a mad dash to somewhere or other – so I began to enthuse about his slow travel philosophy and how everyone should travel like this (let’s put my own inability to do so aside for the moment). He politely let me go on for a bit before interrupting: “The main thing, I think, is that each of us gets satisfaction from our travels. Going so slowly would not suit everyone, it’s just important to know what you want to get out of your trip…”

And, of course, he’s right. But it strikes me that, with websites and magazines churning out lists of “must-sees”, “hot destinations” and “places to see before you die”, it is easy to get distracted and forget how you originally wanted to spend your travel time. Perhaps the best balance to strive for is between keeping an open mind and trying new things, and doing so in a way you find meaningful and fun.

And, of course, he’s right. But it strikes me that, with websites and magazines churning out lists of “must-sees”, “hot destinations” and “places to see before you die”, it is easy to get distracted and forget how you originally wanted to spend your travel time. Perhaps the best balance to strive for is between keeping an open mind and trying new things, and doing so in a way you find meaningful and fun.

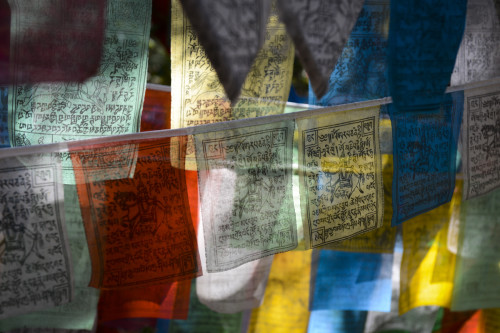

That might mean taking the time to hunt down a special flavour of gelato in Florence rather than visiting another church; or sipping a cup of sweet tea in a Yangon teahouse rather than dutifully tramping around another yet pagoda; or blinking in bright sunshine from the roof of the Jokhang in Lhasa, rather than queuing to enter the crowded chapels below. Whatever it is that you enjoy, take time to seek it out and soak in the experience, rather than following crowds or fashion – go your own way.