On my first trip to China I kept hearing rumours about Laos, which at that time – mid-1999 – was still very much off the beaten track.

“The roads are all dirt tracks, and you’ll spend weeks getting rust-red dust out of your hair,” one fellow backpacker told me, knowingly. I had only recently discovered that such a country existed, so these survivors’ stories of epic bus journeys and remote villages combined with my near-absolute ignorance in a way that left me longing to hop over the border and explore.

Distracted by university and work, it wasn’t until 2007 that I finally managed to arrange a trip to Laos. Escaping the greyness of a Beijing winter, my husband and I flew to Kunming, caught a bus to Jinghong and took a minibus to the border at Mohan.

We negotiated our exit from China, and took a van across the few hundred metres of “no man’s land” that separates the two border posts. The Lao checkpoint fitted my idea of how it ought to look perfectly; a series of ramshackle huts where sullen officials stamped our passports with an improbable number of rubber stamps.

Once finished with the formalities, we clambered into a songthaew (an overgrown tuk-tuk where passengers sit facing each other on two benches inside), and drove off into the afternoon sunshine towards Luang Namtha, giddy with the excitement of being somewhere fresh and new.

Once finished with the formalities, we clambered into a songthaew (an overgrown tuk-tuk where passengers sit facing each other on two benches inside), and drove off into the afternoon sunshine towards Luang Namtha, giddy with the excitement of being somewhere fresh and new.

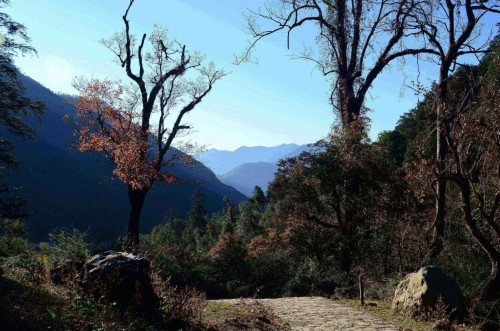

We spent the next five weeks travelling the length of Laos by bus and songthaew. After the border checkpoint had confirmed my expectations, the rest of the country came as a surprise; more beautiful than I had pictured, less developed than I anticipated, and more fun to explore than I had imagined.

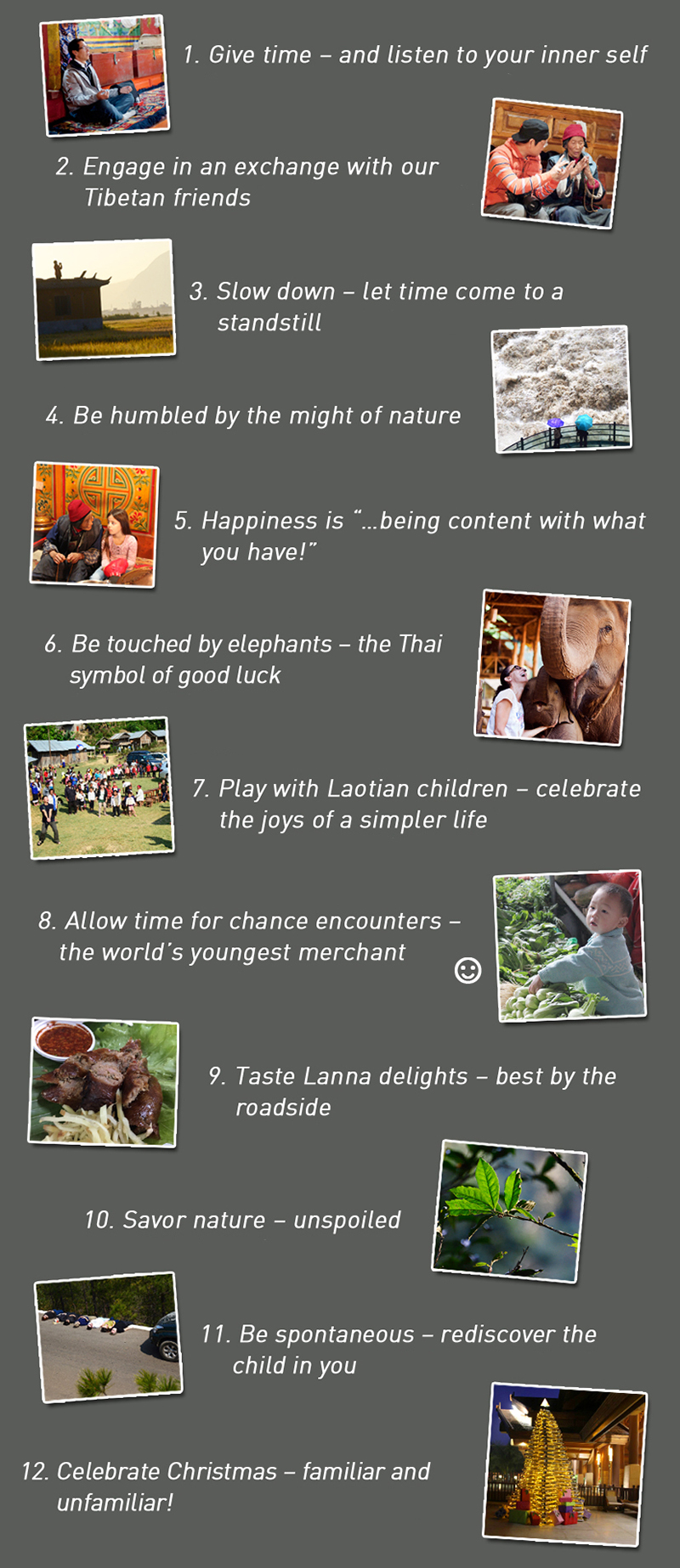

In Luang Namtha we discovered Lao food. In a thatched hut in the rice fields, our hiking guide produced a delicious lunch of herb-filled larb salad and sticky rice all wrapped in banana leaves, a meal that we still talk about to this day. We slurped steaming bowls of rice noodles in a street stall, tried chilli-spiked river fish grilled over an open fire in the night market and breakfasted on baguettes stuffed with cheese and sausage, locally-grown coffee and plates of juicy tropical fruit. Like hobbits, we took to having multiple meals – first and second breakfasts (on one occasion finding space for a third), first and second lunches, dinner and perhaps an evening snack or two.

After travelling through the country’s beautiful, rural north, where villagers’ income seemed to derive from drying grasses to make brooms, we arrived in Luang Prabang one evening to find its colonial villas converted to chic hotels and well-heeled tourists mingling with scruffy backpackers like ourselves in the night market. By day, it was clear to see what had drawn people to this elegant town, its neat grid of streets lined alternately with ornate monasteries and faded Indochinese villas. All this lies nestled amongst forest-clad hills on a tongue of land formed by the confluence of two rivers, the town as blessed by geography as it has been by history.

Father south, the workaday town of Vang Vieng – which grew up around a Vietnam War-era US air strip – had just established itself as a backpackers’ favourite, thanks to its beautiful surroundings and a handful of bars showing Friends on loop. We floated down the Nam Song River in the shadow of jagged limestone karst hills and slept to a chorus of croaking frogs that lived in our hotel’s lily pond.

By the time we reached Vientiane, the monochrome of Beijing’s winter streets was a distant memory. It came as a shock to drive past the country’s only “factory” – a small water bottling plant on the outskirts of the capital – our first brush with anything even remotely industrial since we had left China.

The Laotian capital seemed impossibly small and quiet for a capital city. We cycled along the wide boulevards, dined at the city’s night market and drank Beer Lao as we looked out across the dark waters of the Mekong towards Thailand.

By the time we crossed the border into Thailand a fortnight later – now with survivors’ stories of our own, mostly relating to bus travel – South-East Asia’s only land-locked country had found a place at the top of our list of places to re-visit.

Little did I know that a few years later I would be regularly driving across northern Laos with groups of guests for On the Road. Over the course of many journeys, we’ve seen the Lao infrastructure gradually improve – the shabby border checkpoint has been upgraded and the rickety car ferry that we used to cross the Mekong in Huay Xai has been replaced with a new bridge. Laos is gradually becoming more developed, but, by and large, this is happening in a gentle way – there are no traffic-choked highways or big box shopping malls. The country retains its quiet charm, the Lao people still welcome curious travellers and the food still tastes as good as ever…

On the Road offers several journeys that go through Laos:

- The most in-depth exploration is our all-new “Elephants and Parasols: From Vientiane to the Golden Triangle” itinerary … launching in April 2017!

- Other itineraries that go through northern Laos include:

- “Summit to Sea: From Yunnan to Vietnam“: from the edge of Tibet to the South-China Sea.

- “From Shangri-La to the Lanna Kingdom“: from the edge of Tibet to Chiang Mai in northern Thailand

- “From Yunnan to the Lanna Kingdom“: from Kunming via the UNESCO World Heritage Yuanyang Rice Terraces to northern Thailand