Yunnan’s food is one of China’s most delicious surprises, yet Yunnanese cuisine is not well known outside China. Why is this the case? We look at six foods that define this fascinating and beautiful province.

Too often, Yunnanese cooking overseas is reduced to a single dish – “crossing bridge noodles” (see below for the story behind this dish’s name). Individual bowls of piping hot broth are served along with plates of raw meat, vegetables and noodles that diners tip into the soup to cook. While people from Yunnan certainly do love a bowl of rice noodles, there’s much, much more to food here.

Too often, Yunnanese cooking overseas is reduced to a single dish – “crossing bridge noodles” (see below for the story behind this dish’s name). Individual bowls of piping hot broth are served along with plates of raw meat, vegetables and noodles that diners tip into the soup to cook. While people from Yunnan certainly do love a bowl of rice noodles, there’s much, much more to food here.

Thanks to Yunnan’s varied topography and climate, the province’s markets are filled with a huge range of fresh, seasonal produce. Exotic fruit thrives in the warmth of tropical Xishuangbanna; huge ears of corn ripen in the fertile land around Dali; Dongchuan’s rust red soil produces wonderful potatoes; sweet, crisp apples grow around Lijiang, and fungi with fantastic names (termite mushrooms, anyone?) are dried and exported from Yunnan across Asia.

Each of Yunnan’s ethnic groups puts its own twist on the preparation of these local ingredients. Around Shangri-La, Tibetan cooks flavor dishes with dried peppers and cumin; the Drung of the Salween Valley traditionally cook on heated stones; Xishuangbanna’s Dai people enjoy a combination of intense chili heat and pickled sourness that can make a good Dai meal feel like an assault on the tastebuds.

All this variety makes Yunnanese food tricky to define. Indeed, one reason why Yunnanese food is little-known outside its home territory is that there’s little agreement over what exactly Yunnanese cuisine is – besides crossing bridge noodles, that is. Another reason is that many of the more unusual ingredients are downright impossible to find outside of south-west China – from fishwort roots (折耳根) to bee pupae. However, such exotic things don’t really tell the story of the province. These, more humble, everyday foods do:

1. Rice

Rice in one of its forms – steamed rice, sticky rice or rice noodles – is the core of most Yunnanese meals. Tiers of rice paddies that have been carefully maintained by generations of farmers are a testament to the crop’s importance, especially in the south-east of Yunnan, home of Yuanyang’s spectacular “ladder fields”.

Rice in one of its forms – steamed rice, sticky rice or rice noodles – is the core of most Yunnanese meals. Tiers of rice paddies that have been carefully maintained by generations of farmers are a testament to the crop’s importance, especially in the south-east of Yunnan, home of Yuanyang’s spectacular “ladder fields”.

Rice noodles have evolved into many different varieties in Yunnan (flat ones, round ones, thick ones, skinny ones, soft ones, chewy ones), and are especially popular at breakfast time, when they are served in soup and topped with ground meat, fresh herbs and lashings of chili. It’s worth seeking out a Yunnanese special – ersi made from cooked rice, which gives the noodles an unusual (and delightful) chewy texture.

It’s also worth making a fairly long detour to try Dai pineapple rice in Xishuangbanna. Soaked sticky rice is mixed with the flesh of a ripe pineapple and steamed inside the pineapple shell, producing a nectar-sweet antidote to the chili-fueled heat of the typical Dai meal. Which brings us to…

2. Chili peppers

Sandwiched, as it is, between Sichuan and South-East Asia, it is unsurprising that Yunnan shares its neighbours’ love affair with the chili pepper. On an early On the Road trip, the lead car was scene of a heated and protracted debate between our Yunnanese guide and Sichuanese driver as to which province’s food was the hotter.

The jury may still be out on that important question, but dried and fresh chilies as well as mouth-numbing Sichuan pepper are all used frequently in Yunnanese kitchens. Happily for the faint of palate, their addition is often optional – a saucer of chopped chili or chili sauce placed on the table.

The jury may still be out on that important question, but dried and fresh chilies as well as mouth-numbing Sichuan pepper are all used frequently in Yunnanese kitchens. Happily for the faint of palate, their addition is often optional – a saucer of chopped chili or chili sauce placed on the table.

3. Mushrooms

A remarkable 800 varieties of edible mushroom (from a total of 3,000 known types worldwide) can be found in Yunnan, the region being a biodiversity hotspot for fungi, as well as plants and animals. Some are familiar – porcini, chanterelles, summer truffles – while others are decidedly less common – tripe-like zhusun and poisonous-looking green cap mushrooms, for example.

King of them all, however, is the songrong or matsutake, prized in Japan (where it commands prices of up to US$1000 per pound) for its fragrance and meaty texture. In local homes, fresh mushrooms will be simply stir-fried with a little bacon and slices of fresh green chili, but in Kunming’s restaurants the preparation is altogether more sophisticated, with songrong topping a slab of foie gras or a delicate steamed custard.

King of them all, however, is the songrong or matsutake, prized in Japan (where it commands prices of up to US$1000 per pound) for its fragrance and meaty texture. In local homes, fresh mushrooms will be simply stir-fried with a little bacon and slices of fresh green chili, but in Kunming’s restaurants the preparation is altogether more sophisticated, with songrong topping a slab of foie gras or a delicate steamed custard.

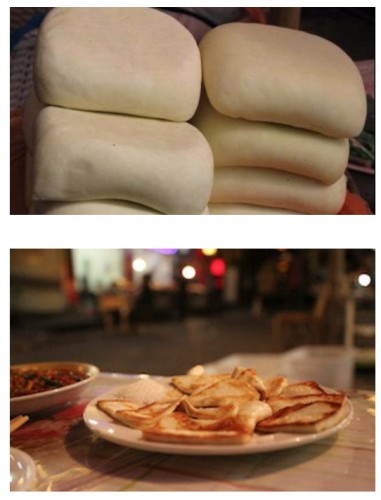

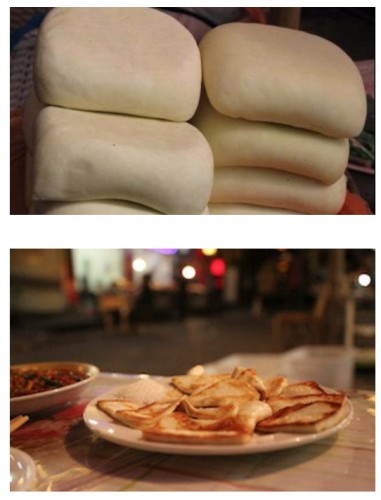

4. Cheese

Unusually for China, two ethnic groups in Yunnan have been producing and consuming cheese for centuries. Separated by 500km of non-cheese eating minorities, the Bai and Sani may have developed their cheese-making techniques and traditions in isolation.

Unusually for China, two ethnic groups in Yunnan have been producing and consuming cheese for centuries. Separated by 500km of non-cheese eating minorities, the Bai and Sani may have developed their cheese-making techniques and traditions in isolation.

However, one tantalizing theory has the Mongolian armies of Kublai Khan introducing cheese-making in the wake of their invasion of the Dali Kingdom in the mid-thirteenth century. (Amazingly, there are still ethnic Mongolian communities in Yunnan today – the descendants of the Khan’s garrisons.)

The Bai of Dali make slabs of white paneer-like rubing from cow’s milk, while the Sani people from Shilin, southeast of Kunming make a similar cheese from sheep’s milk. Rubing is delicious when fried (it doesn’t melt) and sprinkled with salt or sugar. The Bai also make rushan, wafer-thin sheets of cheese that you will see stacked in rolls outside Bai restaurants around Dali.

5. Wind-cured ham

In village houses across northern Yunnan, you’ll often see legs of ham – trotters still attached – lurking in the rafters. As with all the best local foods, there is much competition between counties that claim to produce the most delicious version; Xuanwei’s ham may be the best-known, but the black pigs raised on the banks of the Salween and those from around Lake Erhai are now acknowledged to produce some of the best.

Historically, Yunnan has never been a wealthy province; for many people here, meat had to be used sparingly. Salting and drying pork to preserve it and intensify its flavour was one of the best ways to do this. Typically, slices of ham might be tossed into fried vegetables, served with rubing in a kind of Yunnanese ham and cheese, or in one unusual dish, sizzled on a hot roof tile (瓦掌风肉).

Historically, Yunnan has never been a wealthy province; for many people here, meat had to be used sparingly. Salting and drying pork to preserve it and intensify its flavour was one of the best ways to do this. Typically, slices of ham might be tossed into fried vegetables, served with rubing in a kind of Yunnanese ham and cheese, or in one unusual dish, sizzled on a hot roof tile (瓦掌风肉).

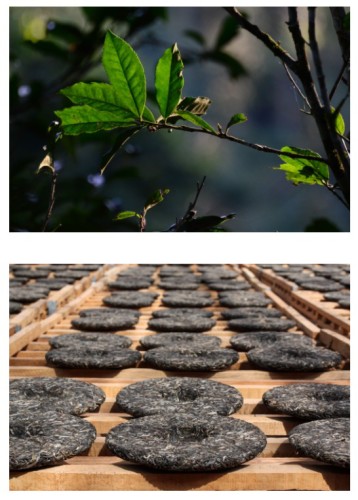

6. Pu’er tea

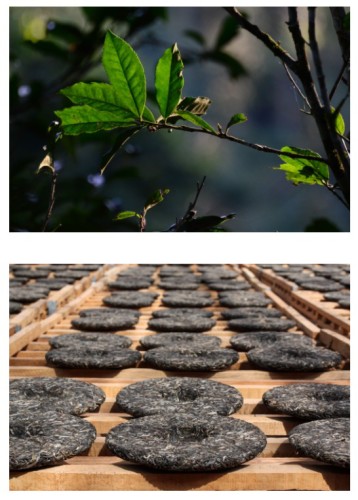

For those of us used to seeing tea bushes in neat ranks, pruned to hip height, the sight of a wizened tea tree deep in tropical jungle seems almost odd. And yet the leaves of these aged trees produce some of the finest tea in the world.

For those of us used to seeing tea bushes in neat ranks, pruned to hip height, the sight of a wizened tea tree deep in tropical jungle seems almost odd. And yet the leaves of these aged trees produce some of the finest tea in the world.

Bricks of tea from southern Yunnan have been exported around Asia for hundreds of years. Leaves of the wild tea trees are dried, fried and steamed into dimpled circles. Once upon a time, these would then be stacked onto mules for the long trek to Tibet. The tea would slowly age on its journey, bringing a depth of flavor that is now much prized – though many accounts of this “tea horse trail” have the Tibetans showing more interest in the tea’s ability to alleviate the effects of a meat-heavy diet, rather than the health-giving qualities we recognize today. Many small towns in north-west Yunnan – Shaxi and Jianchuan, to name two – grew up around overnight stops used by the tea caravans, spreading Pu’er tea’s impact across the province and down the centuries.

*Legend has it that a Qing-dynasty scholar retired to Mengzi in south-east Yunnan where he spent each day in a lakeside pavilion, writing poetry. His wife brought him noodles for lunch each day. The noodle soup cooled on the walk between kitchen and pavilion until she hit upon the idea of topping the broth with a layer of oil, thus sealing in the heat for her journey.

Explore Yunnan’s foods with our journeys…

Adventures in Yunnan will take you and your family through some of Yunnan’s best loved destinations like Dali, Lijiang and Shangri-La and via some little-known gems on an itinerary designed specifically for families to enjoy together.

Adventures in Yunnan will take you and your family through some of Yunnan’s best loved destinations like Dali, Lijiang and Shangri-La and via some little-known gems on an itinerary designed specifically for families to enjoy together.

- 10-day journey

- Kunming – Dali/Xizhou – Shaxi – Tacheng – Shangri-La – Lijiang

- Journey Dossier

Family Adventures: Travel Photography in Yunnan is a family holiday you will never forget, a chance to discover new lands and people and to engage with a hobby – photography! – that may become a lifelong, shared passion among parents and children.

Family Adventures: Travel Photography in Yunnan is a family holiday you will never forget, a chance to discover new lands and people and to engage with a hobby – photography! – that may become a lifelong, shared passion among parents and children.

- 10-day journey

- Kunming – Dali/Xizhou – Lijiang – Tacheng – Shangri-La

- Journey Dossier

Searching for Shangri-La takes you on back roads through Yunnan’s less well-known village treasures to the edge of Tibet

Searching for Shangri-La takes you on back roads through Yunnan’s less well-known village treasures to the edge of Tibet

- 9-day journey

- Kunming – Dali/Xizhou – Shaxi – Tacheng – Deqin – Shangri-La – Lijiang

- Journey Dossier

Shangri-La to the Lanna Kingdom will take you from ethnically Tibetan Shangri-La to the tropical heart of the Golden Triangle, then on to Chiang Mai in Thailand – former capital of the ancient Lanna Kingdom.

Shangri-La to the Lanna Kingdom will take you from ethnically Tibetan Shangri-La to the tropical heart of the Golden Triangle, then on to Chiang Mai in Thailand – former capital of the ancient Lanna Kingdom.

- 12-day journey

- Kunming – Lijiang – Xizhou – Xishuangbanna – Luang Namtha – Chiang Sean – Chiang Mai

- Journey Dossier

Yunnan through a Lens: Tea Horse Trails – capture memories as beautiful as the landscape on this photographic journey through breath-taking north-west Yunnan.

Yunnan through a Lens: Tea Horse Trails – capture memories as beautiful as the landscape on this photographic journey through breath-taking north-west Yunnan.

- 9-day journey

- Kunming – Xizhou – Lijiang – Tacheng – Shangri-La

- Journey Dossier

Go on a Family Holiday you will never forget!

Go on a Family Holiday you will never forget!